In this post I will cover my first two weeks of fieldwork. I haven’t had – and I won’t have – time to properly process interview data while I’m here. As such, the next few blogs will be some spontaneous reflections on themes which are emerging as I go on.

In this post, I will go in a rough chronological order but choose to talk about themes rather than specific interviews, both in the interests of brevity and also some issues around confidentiality. For now, I have also chosen to leave out specific place names – though I will be more specific in more official research outputs. The purpose of this blog is not a landslide inventory or a scientific database, but rather to highlight the wider context and contestations involved in landslides at different stages of their evolution. There are, however, some aspects/themes that I may hold back on discussing at length, as I need to really think carefully about how I present and frame some of the more sensitive issues. At the end of the post I draw the main themes of the post together and also discuss the enjoyable and challenging aspects of this type of research.

Friday 01/11 – Monday 4/11:

Friday was my first full day back in Kalimpong after visiting Kolkata. I spent much of the day in Café Kalimpong, meeting up with Lochan, who would now be my research assistant for the next couple of months. We had a long meeting in the afternoon where we discussed my research, the main themes I’m looking into, our schedules for the coming months, and generally devising a strategy for the coming weeks.

Methodology/strategy:

With the plan roughly sketched out and Lochan’s roles roughly outlined, we agreed to start work on Tuesday, as he was busy on Monday. The plan for the next 3.5 weeks – after which I was taking 2 weeks off because my girlfriend is visiting – was speaking to people who have experienced or witnessed landslide events, or who have been affected by them in some way. We would use the sources I had found over the past few months to identify areas round the district that were affected by landslides. Lochan would then use his contacts in these areas to see if they knew anyone affected, or at least where the landslides were specifically. Failing a contact, we would either approach the areas through institutions like schools and churches, or simply ask people on arrival. Generally, the approach could be classed as snowballing. We are deliberately avoiding approaching people through government agencies and/or political parties, so people didn’t feel coerced into participant and so the messages we receive aren’t politically biased in some way. Our approach doesn’t remove the risk of a political bias, but it certainly reduces it. Thus far, the interviews could be split into two rough parts. The first relating to what these people think caused the landslide, who responded, and what has been done about it since – and everything in between. The second part relates more generally to the changes they have seen in their local environment over the years, and also how they imagine it will be in the future. The last point is of particular interest, as it helps to map out the possible futures people foresee for their locality and the area more generally, as well as the contestations between these different imaginations. This also helps to paint a picture of how people feel that risk – relating to landslides, earthquakes and other phenomena – is managed, or not managed. The interviews are semi-structured, where the conversation is allowed to flow but key questions and themes are discussed in each. So far, the process has been complemented by people showing us round their home and surrounding area to help paint a picture of past events and/or future risks. This gives a bit more substance to the interviews. In some cases, Lochan and I have also walked around various areas ourselves to get a feel for some of landscape and see some of the main features people may refer to in interviews, take photos, and generally improve our understanding.

A relaxed weekend followed where I can’t recollect any extraordinary events happening!

Monday 04/11/19

I had a free day on Monday as Lochan was busy. As usual, I went to the café and met a friend there, managing to get some reading done too. That afternoon, around 3pm, my friend and I noticed a menacing cloud creeping over Deolo hill, which dominates the view of Kalimpong from the café’s open seating area.

A few minutes later, there was a flash of lightening and an almost instant loud thunderclap. A few minutes later, the torrential rain of the storm had swept over the café. We were sat right at the outside edge of the seating area and were soon forced to move further inwards – along with most of the café customers. 90 mins+ of this extremely heavy rain followed; a few unlucky souls dived into the café out of the rain, soaked to the skin. The road outside became a river, with inches of water hurtling down towards the town, carrying branches, solid waste and pebbles with it – seen in this video. The power also went down, something which happened all around this locality. The next day, we heard that Kalimpong had received 31mm of rainfall over 2 hours or so and was in fact the only place in the whole of West Bengal where it rained.

There was no forecast for this rain, it had arrived after 3-4 and a half days of sunshine, and really came out of nowhere. Un-forecasted rainfall is common in the The Hills. Events such as this serve as a reminder that early-warning about heavy rainfall and associated landslides is not a panacea for disaster risk reduction here, or anywhere for that matter. This event also highlighted the interconnected nature of risk in Kalimpong. The flooding was undoubtedly made worse by two other factors associated with urbanity. The first was solid waste blocking drains which was evident by the amount of water flowing down the roads. This also has a more long lasting effect. Water which is blocked is diverted onto the roads, where it subsequently erodes the tarmac/concrete and creates potholed/rough roads, and/or can erode the banks on the sides of roads, which can lead to small landslides all along the roadside.

Second, and perhaps more influential, is Kalimpong’s increasingly concretised landscape. This increases run-off into drains and ultimately onto roads and into places where the water can cause damage. Both of these factors have already had impacts on homes and businesses. An example is provided in this video from this year’s monsoon season. Here, a house was built on top of a drain. Over time, plastic waste was carried through the drain and became blocked underneath the house – meaning it could not be unblocked. During a heavy shower, the water became diverted out of the drain and ended up flowing through someone’s house onto the parallel street below. The home/business happened to sell gas canisters, which are seen flying down the stairs, carried by the water. I believe that ultimately, people had to destroy a wall of the house in order to unblock the drain. These kinds of small but complex and interconnected events are now common in an urbanising Kalimpong, and show that early warnings and ‘preparedness’ alone are not enough. Without stronger enforcement of planning laws and improved waste management, at both the individual and state level, these events will continue to take place.

The rain eventually stuttered to a halt, and I was able to safely take the short walk home.

First week of interviews:

For the first week or two, Lochan and I decided to stick to areas that are close to or in the municipal area of Kalimpong. What I soon realised, though, was that this did not mean that we would be looking into urban areas only. Here, the transition between small city and remote rural village can sometimes feel instantaneous. Many areas of Kalimpong are not accessible by road. To reach some villages that are less than 2km from the centre of town can take well over an hour. One common theme which has emerged so far, though, is that this is beginning to change. Both the central and state governments have made road connectivity a key policy to sell to voters, promising ‘jeepable roads’ to link up the most remote villages with main roads – though this is not without problems, which I will discuss later. These programmes have been in existence for almost 20 years, for example the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) (Prime Minister’s Rural Roads Scheme), which was commissioned in the year 2000. However, this is not to suggest that all of these villages have roads, or at least usable ones.

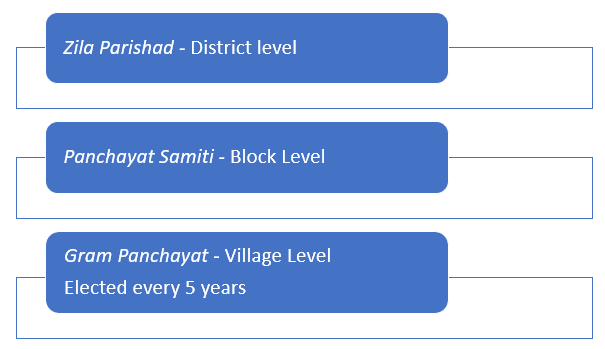

Where roads haven’t been constructed due to either a lack of political will or because a road simply isn’t feasible – usually due to the gradient – villages have other options. For example, they will often make use of the Mahatma Gandhi Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA) programme – otherwise known as ‘100-days work’ – to acquire funding to build concrete steps between their houses and main roads, or between houses. The act guarantees rural households with 100 days of paid employment per year, with the funds usually used to allow locals to build small infrastructures in their locality. These funds are generally allocated through the panchayat structure. Lochan and I have now traversed so many of these steps that we have renamed MGNREGA as the ‘stairway grant’ – you can tell they are funded by the programme as there is almost always some kind of sign signalling that this is the case.

In other cases, there are other ‘main roads’ being built, often as bypasses or alternative routes, presumably with a view to relieving the strain on the narrow roads which cut through Kalimpong and connect much of the district to the plain areas. There is another motive for these roads too. As I have touched on previously, Kalimpong is a heavily militarised area, not in the sense that the population need to be subdued, more because of its proximity to the Chinese border. Many of the roads to the border points in Sikkim, such as Nathu-la, cut through Kalimpong – there are also a number of bases in the district. Huge army trucks are a common sight, and many of the roads are being constructed with a view to providing these trucks with alternative routes to the heavily manned border. Whilst these are often positive developments for the region, they don’t come without risks. One journalist told me that ‘if China are building more and bigger roads to the border, so is India – and vice versa’.

Big roads, big landslides:

Our first visit was to an area where such a new main road was being built, though it is as yet unfinished, apparently due to a legal dispute. The road was built with a view to relieving some of the traffic moving through the town, so as to provide an alternative route for the military and traders to reach the rest of the district without getting caught up in the congested town. In the monsoon of 2015, a landslide occurred below a newly constructed section of the road. The landslide killed 4 members of one family. 2015 was the last time anyone died due to a landslide in Kalimpong, with a few fatalities being recorded during that monsoon. Using various sources, we would try and visit many of the landslide areas from that year. On arrival at the place of the landslide described above, we asked some locals chatting at a shop where the landslide was, which turned out to be right where we were speaking to them. Lochan asked them about their recollection of the landslide. They said that a smaller landslide further up the hill had blocked a drain and caused the water to divert down some nearby stairs. The water then flowed over the road and onto the land which eventually gave way. They suggested that the defence wall at the side of the road hadn’t been built well and allowed the water to absorb into the slope below. We were told by everyone we spoke to that there were never any landslides in this area before the road was built.

A few of these people had been the first to respond to the landslide, and recounted the moments and days following. One of the victims was never found. They suggested we could speak to a relative of the family who lived just below where the landslide reached. We would not end up doing a recorded interview with them but we did have a long conversation where I took notes. It would turn out that they also lost a lot of land because of the landslide. However, like many people we have spoken to thus far, they have not received any compensation for the loss of land, both an economic asset and a source of food for many here. My friend Praful, who runs a local NGO who do work on landslides, has often talked about this as a blackspot within the landslide response policy. Compensation can be sought for property damage, death and injury, but appears to not cover land-loss. Having now spent a few weeks doing this research, it is certainly a recurring theme, and one I’m sure that I’ll write about more over the coming weeks.

The following week, we would come across another of these large-scale road constructions which was currently unfinished – though I think this one is still actually in the process of being built. The road had already caused a number of small landslides along the road. A local journalist had covered this road construction and described how one group of houses had been put at risk from the road potentially unsettling a large boulder above their house. We can’t recall seeing this, but the report was from last year so it may have been addressed since then. We do know that at the time of writing, the boulder was still there, and the monsoon was on-going. One of the worst affected areas is where the road cuts across a jhora in the hillside. Many metres below, an old footbridge can be seen. The road now cuts into the hillside and has evidently caused a number of landslides in this small gorge. It is difficult to see how these can be prevented without a huge amount of investment – which is seldom provided. This area is photographed below.

This area is not as heavily populated as other areas of Kalimpong, but there are a number of small villages and homesteads dotted along the road. Again, there are trade-offs between a boost to connectivity and the risk created through road construction. The boost in connectivity would be particularly useful for schoolchildren, one of which we spoke to on our walk, who have to walk a long distance along this road to and from the carpeted road where they can be picked up and driven to school. The journalist mentions how these children take two sets of clothes to school during the monsoon season, as they usually get very wet. Conversely, there is also an issue of exposure of the children to falling boulders and landslides during the rainy season. It is possible to have the connectivity without the risk, though this requires road construction which is completed quickly, properly funded, constructed with a view to preventing landslides and ultimately done professionally. Unfortunately, it can be said that almost none of these things are happening. I have chosen to wait to present these reasons why until I complete my fieldwork and am able to present them in my thesis and other publications. This is because my study is on-going and it is important that I reflect on how to frame these issues carefully when I have as much information as possible. For now, it can simply be said that it is difficult to separate the creation of landslide risk due to road construction from political processes; processes which relate to the local area, the state, the country and the legacy of colonialism.

Small roads and access issues:

For the next two days, we visited another rural area which was very close to the municipal area of Kalimpong. There are main two landslide-related issues for this area. The first relates to access. The village is most easily accessed via a footpath from the main road. This footpath bridges four jhoras (rivulets). The water flow through these jhoras is becoming stronger due to both the rapid urbanisation of the town at the top of the hill, as well as a general change in rainfall patterns. Everyone we have spoken to so far has said that the monsoon rains are falling in more intense, short downpours these days, as opposed to the lighter and longer lasting rains of earlier years. This could be linked to climate change related to anthropogenic processes across the globe, though there needs to be more research on this specific linkage. Because of the type of rock/soil, these strong currents erode the jhoras with ease during the monsoon season. This has resulted not only in wider jhoras, but also more jhoras, with whole new channels being carved out by the torrents of water – one of these new channels has only been around a few years. During the 4-5 month monsoon season, these jhoras often become impassable, with weak bamboo bridges often being washed away.

Even the very recent (a year or two) concrete bridges are showing signs that they will give away sooner rather than later. We are told that people have lost their lives crossing these jhoras in the past.

The alternative route to the town, up the hillside and away from transport, is much longer and probably not much easier during the monsoon season. The result is that children often miss school, taxi drivers can’t do their work, people requiring medical attention are made more vulnerable, people are unable to buy necessities; and ultimately, people’s lives become much more difficult.

The second landslide related issue is that this particular area is a ‘sinking zone’. Essentially, the whole part of this hillslope is slowly slipping down into the Teesta river below. One man we interviewed pointed to a house on the other side of the main jhora cutting down the hillside and said ‘when I was a kid, around 30 years ago, we were level with that house’. We were now stood 20-30m lower than that house. The residents are aware of this sinking issue, and that there is a risk that in an extreme rainfall event or an earthquake, there could be significant slope failure – though this is very uncertain. Further, many landowners here have seen their land become infertile due to the changing geological structure of the land and soil beneath. Some springs have also moved/dried up, affecting people’s water supplies.

As such, many have moved away from this location. Some were able to secure funds to acquire land and build elsewhere. Most moved away to a temporary settlement in an area owned by the forest department, technically illegally. The life here was not much better, without basic facilities, right by the roadside, and generally not as spacious/nice looking as this area, which boasts stunning views and plenty of space. Further, this is an ancestral home for many here and the impacts on livelihoods are more of a ‘slow-burn’, meaning that day-to-day life — for most of the year — can carry on mostly as normal. As a result, many have since decided to move back to their original home and live with the risk of a major landslide. This doesn’t seem to play on the minds of the people here too much. One said that he’s not worried as he’s been here 30 years and there’s no indication of any huge problems. The main reason why people moved, and the problem they remain most concerned about, is not the distant risk of a major disaster, but the problem outlined above – accessibility.

The people here have been complaining to the authorities about their predicament for many years. Their demands are properly constructed footbridges and/or an alternative road to link up the village to another nearby road on the alternative routes. All that they have received so far is a couple of substandard bridge constructions and 90 metres of road (pictured above) to one group of houses, where 1km+ is really required. The people here feel that the government doesn’t really care about them enough for them to invest in these infrastructures. The area is not economically productive and there is no real political incentive for this level of investment. Within this vacuum of assertive action from the authorities – either state or Gorkhaland Territrorial Administration – the community has taken matters into their own hands. A year or so ago, they noticed that a JCB was clearing the 90m of road commissioned by the government. They quickly did a whip round, and paid the JCB to excavate a few hundred metres or so down the hillside. This road is now what people here would say is ‘jeepable’. This road connected maybe 60% of the village(s) to a concrete road at the top of the hill.

The remaining 40%, further down the hill, then saw a similar opportunity. They clubbed together and then excavated what you might describe as the ‘outline of a road’. Lochan and I walked this stretch and agreed that you might just about get a monster truck up it!

Based upon what I have noticed thus far, and according has been raised by other researchers, road construction is a major factors in creating landslide risk in The Himalayas. This is especially the case when the road construction is unplanned and carried out by non-professionals on limited budgets. Already on this road, after 2 months of existence and next to one of our interviewee’s homes, a small landslide has occurred and blocked ‘the road’. It is also worth noting that this road construction is taking place on a sinking hillslope. In the interview with the person whose house was next to the landslide, we had an interesting discussion. This young person was hoping to open a homestay here, where he would serve the locally grown vegetables and provide an ‘authentic’ experience for visitors. He also complains about the accessibility issues and the lack of government attention they receive, but also didn’t want to leave his home. In the absence of an elected panchayat representative, which he suggested could go a long way to addressing the accessibility issues, he said that (paraphrasing): ‘if we (the local community) can show that this place is an economic asset to the local government (by creating a tourism economy), maybe they’ll listen to us and give us some money for a proper road and/or build some proper bridges’.

Here, it can be seen that small risks are being created by unplanned, under-funded and unprofessional infrastructure development, which has materialised in the absence of elected/accountable local government and in reaction to a government which is motivated primarily be revenue generation as opposed to sustainability and risk reduction. It is difficult to blame the people here for sacrificing the creation of what is a fairly small amount of landslide risk in favour of enhancing their own livelihoods. What is questionable, is whether it is right that their right to the receipt of support from the government should be based on profitability, especially when they pay taxes and land revenues to those who would provide that support.

Urban landslides:

As we were spending much of the first 2 weeks in and around the municipal area of Kalimpong, we also covered a couple of landslides which could be considered to be firmly within the urban area of Kalimpong town. According to the 2011 census, the population of this town is 49,000. However, this number was calculated nearly 10 years ago and probably missed a significant number of undocumented residents. Lochan and I both agreed that by now, the number is probably pushing 100,000 – much of this down to immigration. Either way, the urban area of Kalimpong is heavily concretised, clogged up with traffic and absolutely jam-packed full of people. Many people are moving into the town from the rural village or ‘bustee’ areas and building houses wherever they can squeeze in. We had information about a landslide that occurred in 2015 in the town area. Sadly, a young couple were killed by the landslide. On arriving, we ended up chatting to a local resident who pointed out where the landslide occurred and where the affected household used to be – it was just next to his house. We ended up interviewing him. It turned out that he and his family had moved into this area at the same time as the couple who lost their lives. They were not aware of any landslide risk when they moved. During another interview with another lady living below the landslide, who was only affected in a small way, we heard that there had been previous landslides in the area in 1968 and 2009. Having lived there for a long time, the family was able to provide some more context. They said that the main problem was related to poor drainage and concretisation further up the hill, which channelized the water and diverted it onto the land which eventually gave way during a period of heavy rainfall in 2015. This was also exacerbated by plastic waste. Another possible cause is that the land itself may have been dumped there many decades ago, following the excavation of land for the construction of a monastery. As a result, the land itself is possibly sitting on top of a more solid bedrock. After the interview, we went and looked at the area above the landslide zone, which was heavily built upon. Cracks in the concrete were also visible.

The residents below fear there may be another landslide here in future, suggesting that 2/3 of the area has already gone in 2009 and 2015 – they worry the 3rd area may also give way. The 2nd house we spoke to described that the response from the local authorities has been almost non-existent for them, but that the family of the deceased was compensated. A common theme emerging is that unless landslides cause casualties and/or destroy properties completely, the support provided and attention given to the long-term concerns of people who feel at risk is negligible. One reason for this could be that the policies and frameworks in place to deal with problems relating to landslide impacts are limited. Support is available for reconstruction and compensation for casualties, but not much more, other than the provision of tarpaulins. On tarpaulins, one man told us that in recent years, one has had to complete an application form to receive tarpaulins, and that the process can take a day to complete if one has to travel to the block office. He was a day labourer and relied on a daily wage. After a few small landslides, he realised it was cheaper for him to just buy a tarpaulin than to miss a day’s work to get one for free. Returning to the limited policy frameworks, even the reconstruction payments take a long time to process as the application has to pass through the district administration, the GTA structure and an office in Kolkata before it is processed – this can take 6 months. For small damages, sometimes the applications aren’t accepted and/or the amount is negligible. The lady in the urban landslide area told us that in 2009, they received 2000 INR compensation for a whole room of their house being destroyed by a landslide – about £20. She suspected there was corruption involved. Further, it seems that if the landslide area is not under the ownership of the affected person, it also becomes difficult for people to raise concerns and facilitate preventative work on the area that would affect them in the event of a landslide. These people have long asked for a preventive wall to be built and/or proper drainage to be installed. The former has never materialised and the latter has only been partially completed – though it took the 2015 landslide to kick the concerned authorities into action. Preventive work is seldom undertaken here, if it is said that preventive work post-landslide doesn’t count! It is interesting to note, however, that there are certainly political incentives for the local authorities to undertake mitigation work post-landslide – i.e. votes and the perception that the given party will help you. It is an open question as to whether (real) prevention work could be incentivised in the same way – why not? It is another question as to whether this is the right way of doing things!

Drawing the themes together:

I have only covered a few issues here but have chosen to explain the complexities and contestations involved with the creation of landslide risk, efforts taken to reduce landslide risk as well as the issues involved with responding to the materialisation of landslide risk. In my next blog I will cover some other issues, as I have actually completed another 2 weeks of fieldwork in the time it has taken me to write this post about the first 2 weeks! I will now summarise some the main things to take away from this post:

- In almost all cases so far, it is difficult to argue that the components involved in the materialisation of the landslide were solely related to the physical environment – i.e. without any components relating to anthropogenic processes. There is a large degree of variation, but to assume that landslides are purely natural events from the outset will lead to an incomplete framing of the issue

- Each landslide event has been unique in some way. Of course there are common themes which emerge in relation to why landslides happen, such as: poor/inadequate drainage which may or may not have been impeded by plastic/solid waste; poor road construction, existing instability (often traced back to the major rainfall/landslide event of 1968), earthquake tremors; short and heavy rainfall episodes; irresponsible rice paddy irrigation, and increased run-off due to road construction. However, the combination of these components is usually unique and often in ways which are important to understand if efforts to prevent the materialisation of landslide risk is to be avoided. As a result, deterministic framings of disaster risk are unhelpful

- The implication of the above is that the people living in the area have the best understanding of why landslides occur in their area. This is also a result of the size and diversity of the district of Kalimpong, which is difficult to govern from a distance. The current assemblage of institutions means that in most cases, these local voices remain unheard in policy creation and planning. This in itself a factor in risk creation and materialisation.

- The main incentives for the development of physical infrastructure in Kalimpong are revenue creation, geopolitical strategy. It is difficult to separate this development from the creation of landslide risk here.

Final thoughts on the ups and downs of the past few weeks:

The most enjoyable part of the fieldwork has been the people we have met and spoken to. Everyone has been incredibly hospitable, kind, helpful and understanding; despite the hardships so many of them are facing – some of which can be really quite upsetting. This type of research can be difficult as feels extractive and at the point of interview it is difficult to feel like you can really do anything in return. I feel confident in the approach, though, as all the local experts I speak to have encouraged me to take this approach so that those affected can tell their side of the story – the side which is often left out in official narratives. The impacts of landslides are not only felt in the immediate aftermath, but for years and years after the event. These long-term struggles do not receive as much attention as the dramatic immediate impacts, but they are no less severe and certainly deserve more attention, and most importantly action. Understanding and discussing these challenging circumstances has served to really motivate me to make sure that in the long run, my research can help those here in Kalimpong who are already involved in the struggle to highlight and resolve these issues.

I’ll leave you with some photos of the second most enjoyable aspect of the past few weeks, the scenery:

Tarey Bhir Sikkim

A sunset one day

Just a nice view!

Teesta valley at dusk

A cloudy Kanchenjunga

P.S. My next post will be a little delayed as I am taking some time off 😊.